Beauty, Time and Wasting Away

a reflection on our modern obsession with aging, beauty and control

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty, - that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know"

— John Keats, Ode on a Grecian Urn

It’s a funny thing about gray hair, how it doesn’t take to color. The bleach, the tone, the gloss. The gray hair still stubbornly poking through, completely untouched by the chemical process. I got my first grays pretty early, too early perhaps. I assumed it was related to my many vitamin deficiencies when I decided to go vegan some time in 2014. It was the craze then. All those documentaries about meat and how it was ruining the planet. Not at all mentioning the oil and gas industries. No, it was my penchant for ribeye that was doing it.

Whether vitamin deficiencies caused my early grays doesn't matter anymore; I now have well-earned silver strands keeping them company—the mark of age I can't seem to escape. Initially, the gray hair didn't bother me. It was just at the edges. I didn't think too much about it until they began to crop up in new places. Pollinating, it seemed. I suppose this is aging. These silver strands — a harbinger of what was to come.

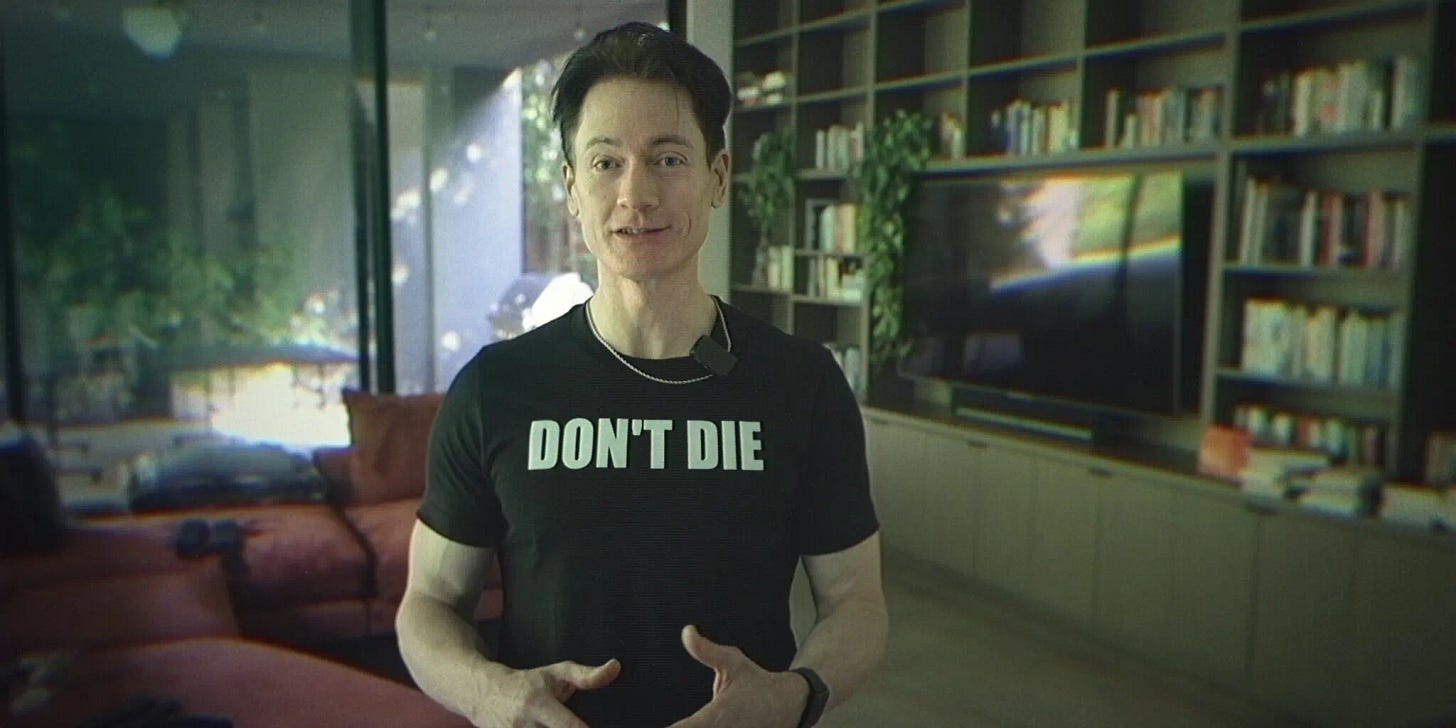

Aging seems to be one of the defining battles of our time. Bryan Johnson, a tech entrepreneur turned human guinea pig, believes we can defeat aging once and for all and theoretically live forever. He takes over 100 supplements a day and collaborates with more than 30 medical professionals in his pursuit of immortality. Recently, I watched a video of Johnson discussing his graying hair, where he adamantly insisted that his hair retains pigmentation at the root, despite regularly coloring it with natural dyes. Gray hair appears to be the ultimate sign of aging, a signal that even Johnson, with his meticulous regimen, can't seem to avoid.

In Western society, beauty is often tied to the appearance of youth, fueling the belief that looking young and "hot" will unlock all your dreams—a view satirized in films like The Substance (2024). This raises an interesting question: Could Bryan Johnson's project at its core be about beauty? While he claims his health regimen is for the benefit of humanity, he spends an exorbitant amount of money experimenting on his own body—a profoundly unscientific endeavor—rather than funding research that could actually advance human health and longevity. It makes me wonder: would Johnson still consider his project a success if he achieved the biomarkers of youth but still looked his age? This is why I suspect his pursuits are not solely about health but also about beauty.

There is something about this pursuit of beauty, especially in the context of youth, that taps into something deeper—our relationship with time itself. Johnson recently undertook a new project he called “Project Babyface.” His goal was to restore volume to his face and tighten his skin. The results, however, were far from glamorous—his face swelled and reddened, a grotesque testament to his vanity, offering a moment of schadenfreude for onlookers. Johnson’s drive for a more youthful look is rooted in the delusion that looking young somehow grants you more time, as if preserving the outward appearance of life could delay its inevitable course.

The thing about beauty is that it is something we all know but can never fully define. It exists within our collective consciousness, an ever-present yet elusive concept. The indefiniteness of beauty is precisely what makes it alluring—why poets dedicate countless verses to describing it. Beauty is wholeness; it resists dissection. Tearing apart a flower to measure its parts doesn’t explain why it moves us.

Scientists have long tried to define beauty, to quantify it. They assign it ratios and measurements: symmetry, the golden ratio, the mathematics of a perfect face. Yet for every rule, there is an exception that defies it. Science may say youth is beautiful, but we often find beauty in age. It tells us beauty is tied to fecundity, but we are captivated by the desiccated elegance of dried flowers pressed between the pages of a book. Even death—wrapped in ritual—holds beauty. In Islam, when someone dies, their body is washed, perfumed, and wrapped, an act of dignity and reverence. Who can deny the beauty in that?

Still, attempts to pin beauty down—to study it, dissect it, define it—are strikingly similar to what Johnson is doing with his desire to escape death. It’s an effort to strip away mystery, to replace our mystical and abstract conceptions of beauty, aging, and life itself with hard, scientific views. To people like Johnson, mystery seems intolerable. The idea that some things are unknowable—that beauty and life may be greater than the sum of their parts—is unsettling. Instead, they believe that with enough research and dissection, everything can be understood, controlled, and manipulated at will.

This view extends beyond Johnson. Figures like Andrew Huberman, who frame wellness and optimization in hyper-scientific, data-heavy terms, and even Kim Kardashian, whose visible fear of aging drives her to extreme beauty measures, all seem to share a rejection of the unknown. Their relentless pursuit of control over their bodies and lives reflects a deep anxiety and a shallow materiality, a fixation on surface-level solutions to deeper, more existential fears. Science becomes their new faith, replacing the rituals of religion and spirituality with data points and protocols.

Those familiar with the tech world know that the roots of this mindset lie firmly in Silicon Valley. It’s no coincidence that Johnson embraced this doctrine after establishing himself as a tech entrepreneur. The dominant worldview in Silicon Valley is one of libertarianism, where individual freedom and deregulation are the norm. Coupled with techno-optimism, this culture believes that all human problems can be solved with enough data. It’s in this environment that fantasies of immortality or uploading consciousness to the cloud thrive. Their worldview strips away mystery and nuance, presenting the belief that with enough resources, science, and technology can create a perfect world free of mystery—a world where every problem has a solution, every unknown is a data point waiting to be discovered, and every limitation can be overcome. This vision holds that with the right tools, we can engineer not only the world but also our very existence, leaving no room for the unpredictable, the unknowable, or the divine.

What’s fascinating about Johnson in particular is how this impulse connects to his rejection of Mormonism. Having left the church, he seems to have replaced its doctrines and dogmas with the philosophy of longevity, his own personal church of optimization. Religious asceticism—the monk’s renunciation of material things or the Muslim’s detachment from Dunya (the material world)—has always been a path to something higher, a way to access a connection to the divine. But Johnson’s asceticism focuses entirely on the material. His protocols mirror the rituals of religion, but they are stripped of mysticism. Instead of praying before dawn, we wake up to meet the sunlight and regulate our systems. Instead of fasting for spiritual growth, we fast to optimize our nervous systems. The rituals remain, but their essence—the mystery, the unknowable, the faith—has been replaced by data points and biomarkers.

Religion teaches us that there will always be things we cannot know, that the divine lies in the gestalt—in something larger than the sum of its parts. Faith is its essence: a trust in the unseen, the intangible. Without mystery, what are we left with? Johnson’s project, and the worldview it reflects, seem unwilling to make peace with this. It insists that with enough effort, enough research, and enough discipline, we can know everything, control everything, and perhaps even transcend our own mortality.

But is life truly life if we strip it of mystery? Is beauty still beautiful if it’s reduced to ratios and symmetry? Maybe the effort to conquer mystery is itself a misunderstanding of what it means to be human. We aren’t meant to understand everything; we’re meant to live in the tension of the known and the unknown. And perhaps that’s where true beauty lies—not in control, but in surrender.

People throughout history have tried to escape the inevitability of time and the constraints of their biology. J.I. Rodale, the founder of the organic food movement, was one such figure. He preached the virtues of longevity, linking diet and health to immortality. In a grim irony, Rodale died of a heart attack while being interviewed on television, a public and undeniable reminder that no amount of organic food could save him from life’s impermanence. The lesson in Rodale’s story isn’t just about mortality but about the futility of trying to dominate something as inexorable as time.

The drive to control, optimize, and extend our lives through technology stems from a worldview that rejects the unknown and embraces only the material. For those who see existence as confined to the physical, the natural conclusion is to subjugate the material world to the will of the individual. It is a cosmology deeply rooted in a fear of mortality and imperfection. The tech world’s relentless pursuit of optimization—whether in the form of anti-aging regimens, genetic manipulation, or the quest for digital immortality—can only be understood as an attempt to avoid the inevitable: the ravages of time and the vulnerability of our bodies. This is not a vision driven by love, by an embrace of life’s fleeting beauty, but rather by a deep-rooted fear of death, decay, and loss. It is the belief that by perfecting the material world and the self, we can outrun the ticking clock and somehow transcend the limits of our physical existence.

But beauty and life are far beyond the grasp of such control. Beauty, in its truest form, is not something that can be manufactured, optimized, or indefinitely preserved. It is fleeting, impermanent, and grounded in the acceptance of time’s passage. This is the heart of true beauty—its vulnerability and transience, which makes it all the more profound. When we seek to hold onto beauty or life as fixed, perfect ideals, we rob them of their true essence. We become so focused on achieving an unattainable ideal—an eternal youth or a flawless image—that we lose sight of the beauty that is already present in the natural cycles of life.

As the tech world becomes more obsessed with the perfectibility of the human body and mind, poets and mystics, those who once held the space for the unknown, for the ineffable, are losing their footing. There is a danger in losing sight of the mystery, the magic, and the messiness that make life rich and meaningful. Mysticism and art remind us that not everything is meant to be understood, optimized, or controlled. There is beauty in surrendering to life as it is, in embracing its uncertainty and imperfection. Poets, philosophers, and mystics teach us that life, love, and beauty are not problems to be solved—they are qualities to be experienced.

Science still cannot explain consciousness, nor can it reconcile why physical beauty and material abundance often fail to bring lasting happiness. While science can describe the chemicals released when we fall in love, it cannot manufacture love itself. This suggests that the material world is not the whole story—that there is something greater than the sum of its parts, a mystery that transcends explanation. Bryan Johnson may extend his lifespan with his array of supplements and strict protocols, but can he ensure a life filled with joy, connection, and meaning?

Rather than adhering to dogmatic ideologies that separate the spiritual from the material, we would be wiser to integrate the wisdom of both realms. Optimizing the material world through technology, health, and innovation has its place, but it must be tempered by the understanding that life cannot be limited to a set of data points. True meaning arises from life’s inherent imperfections, not the pursuit of perfection. We must learn to appreciate existence’s complexity and find beauty in its unknowability.

The pursuit of eternal youth, or even just its illusion, has always been part of the human story. We paint over gray hairs, inject serums into our skin, and adopt stringent health regimens, all in the hope of reversing the markers of time. Yet these efforts only underscore the mystery we try to escape. Gray hair resists dye. Aging marches on. Beauty remains indefinable, and life, at its essence, is uncontrollable.

Gray hair, in its stubbornness, is poetic. It defies our attempts to deny the inevitable, resisting our futile attempts to mask its presence. Like time itself, it pushes through unapologetically, announcing its arrival. Its persistence serves as a quiet reminder that some things cannot be controlled, no matter how hard we try.

Perhaps that’s what unsettles us—not just because it signifies aging, but because it embodies the limits of our power. In a world that constantly seeks to master and manipulate, gray hair stands as an unyielding symbol of life’s inscrutability. It teaches us that beauty does not lie in control or perfection but in the acceptance of what is—in surrendering with grace.

The real poetry, then, may not lie merely in gray hair’s defiance, but in its ability to remind us of our humanity. In surrendering to time, we find a beauty more enduring than youth—a beauty that no science or dye can replicate. A beauty that deepens rather than fades. It is a beauty rooted in our impermanence, an art of living that embraces wholeness—the gestalt—and rejects the shallow materialist boundaries that technologists want to impose on us.

Thank you so much for reading! Please leave a comment, I would super appreciate it. Planning something new for next week, so stay tuned. Till next time!

There's something you touch upon but don't elaborate on in your essay - the idea of tech as a religion/cult, especially in the comparison to Islam and through the story of Johnson leaving Mormonism and replacing it with a new, material worship.

Fascinating piece, thank you for writing it.