Is It Satire or Just Escapism?

how "eat the rich" cinema fails to challenge the status quo and what filmmakers can learn from Ishmael Reed

In the years since Parasite (2019) won Best Picture, Hollywood has leaned heavily into stories that criticize the lives and folly of the ultra-wealthy. Films like The Menu (2022), Triangle of Sadness (2022), Blink Twice (2024), and now Mickey 17 (2025) have all taken aim at the absurdities of the rich. On the surface, this wave of satire seems like a positive step, especially as the wealth gap continues to widen. But somewhere along the way, these films have lost their bite. It makes me wonder how many times we can remake Parasite before the genre starts cannibalizing itself.

When I went to see Mickey 17, it seemed like a promising critique of the capitalist class. The film follows the titular character, Mickey Barnes, and his friend Timo as they set out on a mission to colonize the distant planet Niflheim in an attempt to escape loan sharks after a disastrous business venture on Earth. Mickey's role as an "expendable" places him at the mercy of dangerous missions where his physical body is fatally experimented on. Each time he dies, a new clone of his body is 3D printed and implanted with recovered memories. The film seems primed to comment on the alienation and expendability of working-class people in a capitalist system. Mickey retains the memory of his fatal missions but never enjoys the fruits of his labor. The film also presents a pointed critique of finance capital and its thuggish qualities, forcing debtors to go to extreme lengths to escape its grip.

Where the film doesn’t land for me is through its extremely conventional structure and how the indigenous inhabitants of Niflheim are nothing more than a plot device. The primary antagonist of the film is Kenneth Marshall, a figure that is a blend between Donald Trump and Elon Musk. Marshall naturally has very little regard for the indigenous inhabitants of Niflheim and gravely misjudges their intelligence. However, because the film is focused primarily on Mickey, we don’t learn much about these inhabitants. Their existence functions primarily to push the story forward, but by the conclusion of the film, they don’t seem to have much impact on the humans who colonize their planet. The film focuses much of its runtime on the relationship between Mickey and his girlfriend Nasha. Everything else feels like a backdrop to their love story. In that sense, it is almost a romantic comedy. What I expected in Bong Joon Ho’s follow-up to Parasite was a sharper and more biting satire, but what I got instead was a pretty conventional Hollywood movie.

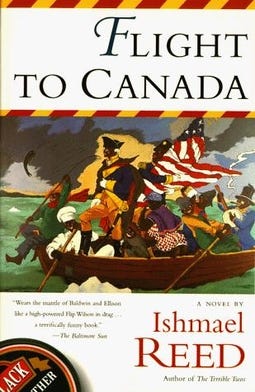

Satire, at its best, works when it distorts reality just enough to expose deeper truths. This is why I keep coming back to the work of Ishmael Reed, one of the sharpest satirists of our time. His novel Flight to Canada is a masterclass in how satire can unsettle our assumptions and reveal the absurdities within systems of power. The novel takes the Civil War era and throws it into a chaotic, anachronistic spin: enslaved people escape by airplane, Lincoln’s assassination happens live on television, and the whole system of power disintegrates in a fevered, looping nightmare. The book doesn’t follow a traditional narrative; instead, it embraces the absurd to uncover something painfully real.

There is a passage from Flight to Canada that exemplifies Reed’s genius and has stayed with me for years. After the plantation owner Arthur Swille dies, he leaves his entire estate to his former slave, Uncle Robin. When Raven Quickskill, the protagonist, asks how this is possible, Robin explains:

Well, if they are not bound to respect our rights, then I'll be damned if we should respect theirs. Fred Douglass said the same thing. Well, anyway, Swille had something called dyslexia. Words came to him scrambled and jumbled. I became his reading and writing. Like a computer, only this computer left itself Swille's whole estate. Property joining forces with property. I left me his whole estate. I'm it, too. Me and it got more it. (pg. 171)

This passage speaks to a truth I’ve seen firsthand. The ultra-wealthy, whether plantation owners or modern-day executives, are often far less equipped to manage the systems they claim dominion over. I’ve worked closely with executives who, despite their status, have far less real-world experience than their interns. Founders who’ve raised millions of dollars but lack any real understanding of how to run a business. I’ve worked with wealthy MBA graduates who barely understand how to read a P&L. And yet, they persist. There’s a mysticism to their power, a “right to rule” mentality that has barely evolved from the divine right of kings. In the past, the justification for slavery was pseudo-scientific racial superiority. Today, it's pseudo-meritocracy that props up a system where the ultra-wealthy act as if they alone are responsible for keeping the world spinning. But when you pull back the curtain, there is very little underpinning their authority. Flight to Canada lays that bare, offering a scathing indictment of the flimsy foundations and fallible figures that uphold systems of power. In contrast, most of today’s “eat the rich” films rely heavily on caricatures and mostly just reflect our current reality, offering little beyond surface-level critique.

Years ago, I got to see a reading of Ishmael Reed’s play The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda. For me, it is another example of his work that demonstrates what can be achieved when creative satire is put to work. In the play, Miranda, after taking Ambien, is visited by the spirits of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and those marginalized by his musical: enslaved Africans, Native Americans, a white indentured servant, and Harriet Tubman. These spirits haunt Miranda in a sense and force him to confront the uncomfortable truths he ignored in his musical. Reed also humorously critiques Miranda’s overreliance on Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography of Hamilton. For context, Chernow has written similarly sympathetic books on Ulysses S. Grant and John D. Rockefeller and has been criticized for presenting overly sanitized views of their legacies. Reed illustrates how Miranda’s dependence on Chernow makes him complicit in the whitewashing of history.

Reed’s critique is not so much about historical accuracy, but a deeper comment on the function of corrupted narratives. Hamilton and Washington were not only influential leaders but also land speculators who sought to acquire Native American land. By obfuscating this part of their history, the musical Hamilton successfully sanitizes the capitalistic goals of the Founding Fathers and adds to their myth. The motivations of the Founding Fathers are central to the creation of the nation, but these corrupted histories make it seem as though they wanted to form a nation out of the goodness of their hearts. The Chernow biography takes this even further, crafting Hamilton as a sympathetic immigrant who was opposed to slavery and motivated by a desire for independence. Never mind that Hamilton wrote pro-slavery letters and supported policies that upheld slavery, Chernow’s telling—and Miranda’s retelling—completely co-opt the modern immigrant narrative to paint a deeply sympathetic and heroic portrait of Hamilton.

What makes Reed’s play brilliant is that it doesn’t just critique Miranda, but also the whole business of using history as entertainment. Through Reed’s portrayal, Miranda's character is nuanced by showing him as a victim of corporate interests, the commercial forces behind Hamilton that have made him a wealthy, celebrated figure. The spirits haunting him highlight Miranda’s role in shaping a narrative for profit, urging him to reconsider the manipulation of history for commercial gain. At one point, the ghost of Hamilton even praises Miranda for rehabilitating his legacy, a moment that shakes Miranda to his core. By the play’s end, Miranda is horrified by his complicity in historical whitewashing and sets out to confront Chernow, who remains unapologetic.

What is notable about Reed’s work is that he doesn’t just mock those he is satirizing; he makes a point to show that they are just human. Rather than reducing his subjects to mere caricatures, Reed emphasizes that even those in positions of power or privilege are shaped by the same human flaws and struggles as anyone else. This approach adds a layer of empathy to his satire, challenging audiences to consider the forces that shape individuals, rather than dismissing them as mere objects of ridicule. Through this lens, Reed’s satire becomes a tool not just for critique but for understanding, offering a path to greater reflection on the societal structures that influence us all.

What’s often missing in much of today’s anti-capitalist satire is a deep sense of compassion, complexity, and, crucially, a forward-looking vision. Many of these films fail to offer the kind of nuanced examination that could inspire real reflection or action. Instead, they act as pressure valves for audiences, giving them a safe space to laugh at the absurdities of the rich and powerful. We laugh at the glaring contradictions, the grotesque excess, and the comical missteps of the wealthy, but this laughter remains hollow. The satire, rather than challenging the systems that prop up the elites, merely reinforces the status quo. It offers a release of tension but provides no momentum for genuine change. In some ways, it doesn’t feel much different than HR office hours, a place where you can be “seen and heard” but nothing ever really changes. The systems that perpetuate wealth disparity, exploitation, and systemic oppression remain unchallenged, leaving the audience with the illusion of progress but no real movement toward it.

The shallowness of the current oeuvre of “eat the rich” films seems to be intentional and mirrors in a lot of ways the elite capture of identity politics. What was once a radical call for change, a demand for justice and equity, has been reworked into a consumable product that loses its power, becoming something palatable for those in power. Just as identity politics has been commodified and reduced to buzzwords and trendy causes, anti-capitalist satire in film is stripped of its revolutionary potential. Instead of challenging the system, it becomes a part of it, absorbed, sanitized, and rendered ineffective.

The process of repackaging critiques dulls their radical edge, transforming them into tools of consumerism rather than vehicles for social change. If satire is going to push us forward, it can’t simply mirror our current conditions; it has to fracture them, subvert them, and reassemble them into something more potent. Reed’s work shows us that satire is not just about critique, but about reimagining reality itself. If filmmakers want to do more than make reheated versions of Parasite, they’d do well to take that lesson to heart.

That’s all for this week. This essay started out much shorter and I meant to include it in an interlude, but it sort of took a mind of its own. All that to say, I love Ishmael Reed and if you haven’t read Flight to Canada, what’s stopping you?? Anyway, Till next time!

I liked Mickey 17! I thought the love story was super sweet. Appreciate the love for Ishmael Reed. I'm reading Mumbo Jumbo right now. Gotta check out his critique of Hamilton. I feel like in 50 years we're gonna find out that Lin Manuel Miranda was actually financed by the CIA whole time.

Love love love! Appreciate where your words took me. I’ve been thinking a lot about what satire might look like now, in this current political climate. Like what if we actually invited comedians to roast politicians, not as spectacle but as a real test of their self-awareness and accountability? I’m thinking of that racist chap at the RNC rally at Madison Square Garden and his joke about Puerto Rico. What would it mean if that kind of critique were the rule, not the exception—but if comedians turned their lens towards candidates? It could make for an interesting exercise. I guess The Onion kind of occupies that lane…