White Men According to R. Crumb

how robert crumb's work lays bare the ugly truths underpinning the psyche of white america

Growing up, my grandparents, who raised me, had strict standards for what could be shown on our television. Most of the time, the screen glowed with the safety of the Discovery Channel or the big cats of Animal Planet. To them, most American shows were obnoxiously loud and vulgar, full of angsty teens and sarcastic adults with attitudes they feared I might absorb. If I wanted to watch the popular sitcoms of those days I would have to do so sneakily, often with the help of my eldest sister. There was one big exception though — cartoons. Whether it was Animaniacs, Hey Arnold, or Daria—they all slipped under the radar. Their vibrant colors and silly voices seemed harmless, unserious, weightless. Nobody paid them much mind. They were one of the few things I could watch completely unsupervised.

That’s the strange thing about cartoons and comics. They slip under the radar. They’re dismissed as kid stuff, and that very dismissal gives them room to move. They can carry messages straight into the bloodstream. In a lot of ways, cartoons are a sort of living archive, packed with symbols, gestures, and caricatures that echo the cultural conditions they were made in. I didn’t have the words for it then, but I could sense there was more going on beneath the surface.

Years later, when I started looking more seriously at the history of American cartoons and comics, that lingering feeling of unease started to take shape. I began to see how deeply rooted these tropes were, how they stretched back to minstrel shows, vaudeville stages, and the early days of mass entertainment. And almost inevitably, that path led me to Robert Crumb.

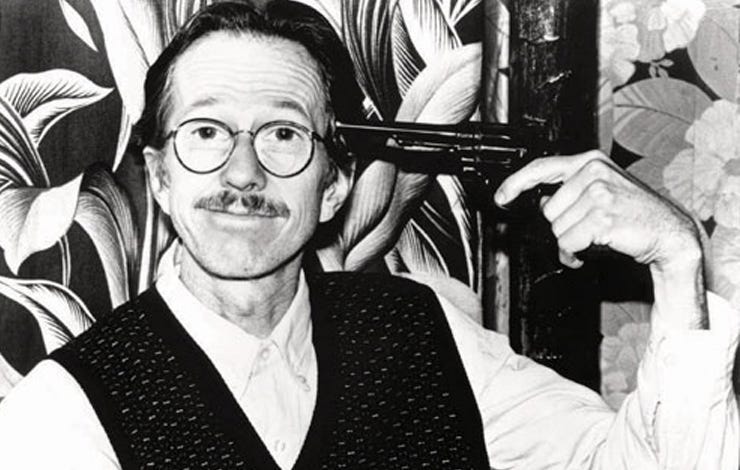

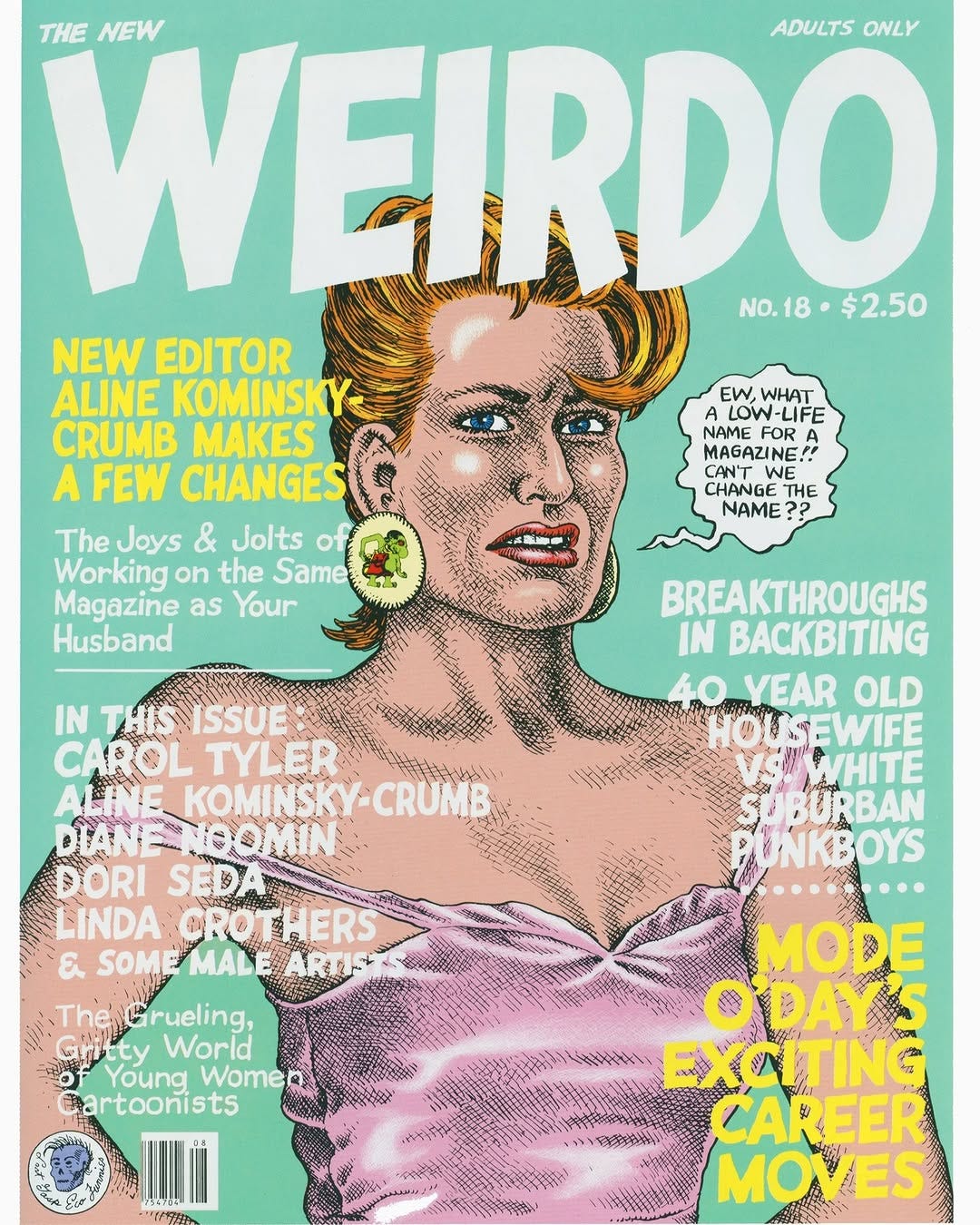

It’s hard to get seriously into comics without running into Crumb’s work. His influence is everywhere. He’s considered a legend, an architect of the underground comix movement. His linework is intricate, obsessive, and hypnotic. His style pulls from the clean, bouncy aesthetic of Carl Barks of Donald Duck fame and the zany satire of Harvey Kurtzman, founder of Mad Magazine. Crumb’s subject matter on the other hand is anything but lighthearted.

I'll be honest, my first reaction to Robert Crumb’s work was visceral repulsion. I was horrified by the caricatures of Black people in his comics. The drawings were so ghastly, so steeped in sexual and racial violence, that they felt less like satire and more like something torn from the ugliest corners of the American imagination. That response, I would later learn, is almost built into Crumb’s project. But at the moment, I wanted nothing to do with it.

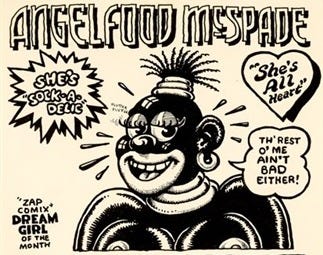

One comic in particular, Angelfood McSpade, made me physically ill. The titular character is a hypersexualized, “primitive” Black woman, drawn with exaggerated features: huge lips, pendulous breasts, thick thighs, and a protruding behind. She’s often naked, speaks in jive, and is portrayed as dumb, naïve, and insatiably sexual—a willing participant in her own degradation. The comic presents her as a joke, but there’s no punchline. The images conjured up in me a familiar ache of seeing Black womanhood flattened, mocked, and offered up for consumption. I could barely stomach it, which is why I initially rejected Crumb’s work wholesale. It triggered my usual aversion to transgression for transgression’s sake, particularly when it punches down.

What eventually made me circle back to his work was Terry Zwigoff’s documentary Crumb (1994). The same queasy feeling I had reading his comics resurfaced while watching his life unfold onscreen. I was surprised to find Crumb to be so sad, misanthropic, and a bit pathetic. He didn’t make any excuses for his art, he knew in a lot of ways it was offensive and alienating. His success seemed even to surprise him.

Crumb was raised Catholic, under the thumb of a pill-addicted mother and a violent, emotionally distant father. His family was soaked in dysfunction. His older brother Charles, who first got Crumb into drawing comics and was exceptionally talented himself, suffered a severe decline in mental health as they grew older—and never recovered. Tormented by his own thoughts and anxieties, Charles eventually took his own life before the documentary was released. Crumb’s younger brother Maxon, on the other hand, lives a vagabond life marked by sexual compulsions and self-denial, often sleeping on floors and begging for food in the name of spiritual purity. In this context, Crumb’s angst and anxiety make a lot of sense. His comics feel like a manifestation of the ills of his family and the larger world that produced them.

Though only briefly mentioned in his documentary, Crumb’s Catholic upbringing struck me as a likely inspiration for his artistic project. Confession is a core aspect of Catholicism, the goal being to rid oneself of sins and find communion with God. In many ways, Crumb’s comics are confessional, and what they confess reveals a great deal about the white boomer psyche and the world that shaped it. The world Crumb grew up in was intensely repressive. The 1950s, in particular, were defined by rigid gender roles, Cold War paranoia, suburban conformity, and a cultural obsession with appearing “normal.” Emotions were tightly controlled, and deviation from the norm was quietly punished or pathologized.

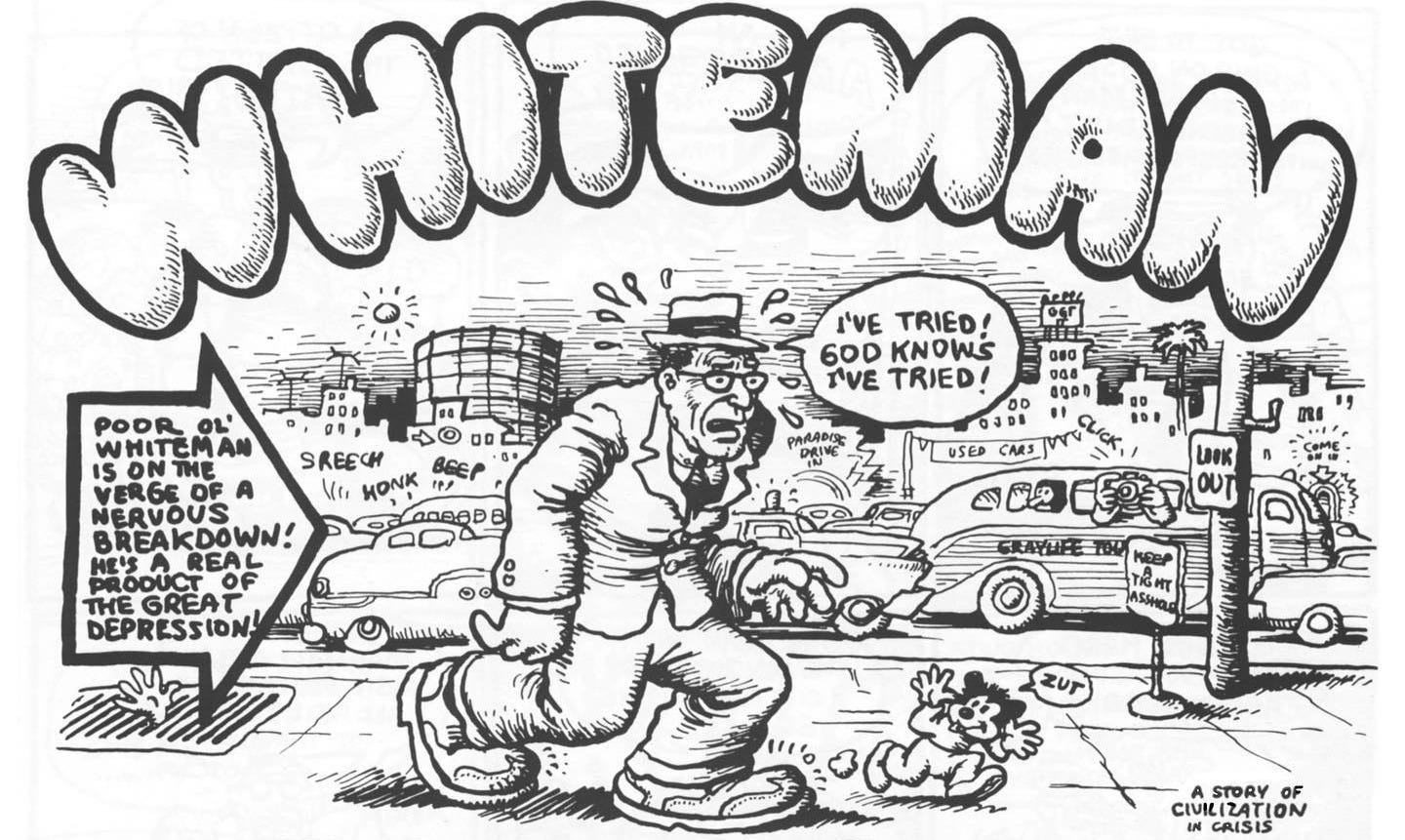

In the documentary, Crumb talks about his father, who wore a permanent grin in public, a mask of macho joviality. Crumb suggests that his father might have suffered from "smile mask syndrome" which is marked by an outward appearance of strength and cheerfulness that hides a caustic emotional turmoil. This kind of emotional repression was a central feature of Crumb’s household, creating an environment of tension that would inevitably shape his work. Crumb's father is also a major inspiration for Crumb’s comic White Man, in which he critiques the emotional and psychological cost of the persona that his father embodied. White Man confronts the oppressive expectations of masculinity and lays bare the toxic emotional landscape that shaped Crumb’s work and perspective.

Crumb’s childhood media diet was also filled with patently racist cartoons, comics, music, and cinema. These images etched themselves into the inner workings of his mind and later spewed back out onto the page. In this way, Crumb’s work reads less like satire and more like a man exorcising demons. This doesn’t absolve him of responsibility, but it does complicate the reading of his work. His comics are not simply about racism or misogyny; they are about what happens when those forces are absorbed, left unexamined, and regurgitated into art. When revisiting his comics, I saw all the gross, ugly bits of American culture laid out plainly. The context of his childhood media diet provided me with a deeper layer of understanding. My family had always been wary of American television and popular culture and unearthing these dark ugly parts of media helped me understand more acutely why they felt that way. Part of why the media I consumed was closely monitored was to avoid falling into the types of media that could make me develop low self-esteem and self-hatred. There was also a fear of being too “Americanized,” which to them meant having a defiant and disrespectful attitude towards your elders and community. In the 90s, my grandparents still retained a small sliver of hope that we would return to Somalia once the country recovered from civil war and so they wanted to preserve in me as much as possible the culture they held so dear.

Looking at the media that Crumb grew up on makes me understand more intimately what my grandparents saw in American society. While the racist history of America is openly acknowledged, much trouble has been done to sanitize the legacies of major media companies and figures. Everyone from Judy Garland to Ted Danson was doing blackface, and the cultural violence is constantly being obfuscated.

Black artists have also, throughout the years, incorporated racist caricatures of Black people into their work as a critique through reappropriation. Artists like Betye Saar have used these caricatures both satirically and earnestly, subverting the harmful stereotypes associated with them and reclaiming power in their reimagination. Jay-Z famously reappropriated Black caricatures in his music video for “The Story of OJ,” using them to comment on racial identity, historical legacy, and the commodification of Black bodies. There is undeniable artistic merit in the reappropriation of these images when done thoughtfully, allowing for a critique of both their original meaning and their continued relevance in contemporary culture.

When Black artists take part in this reappropriation, there is a shared understanding that these representations are not being perpetuated with racist intent, but rather are being reclaimed and transformed into a form of critique. This act of reappropriation allows Black artists to examine the original imagery and challenge its harmful connotations. However, this critical distinction is absent in Crumb’s case. Despite his assertions in multiple interviews that he is not a racist and that his work is meant to exaggerate and satirize, his reappropriation of racist caricatures operates within a far more complex context. Crumb often laments that “PC culture” prevents people from understanding his intentions, yet this defense does not account for the power dynamics that shape his use of such imagery. As a white artist, Crumb’s use of racist and sexist caricatures cannot be divorced from the larger cultural baggage they carry. The images Crumb appropriates do not simply serve as satire or exaggeration; instead, they inevitably perpetuate the very stereotypes they are meant to critique.

This is compounded by the fact that many of the films and characters Crumb references have been erased from the public consciousness. For audiences to fully appreciate the satire of his work, there must be a deep understanding of what he is satirizing. As overtly racist attitudes fell out of fashion in America, there was a concerted effort by major media companies to erase and sanitize the racist history of popular entertainment. The Censored Eleven, a group of eleven Warner Bros. cartoons released between 1931 and 1951, were withdrawn from circulation due to their overtly racist content, which depicted Black Americans and other marginalized groups in demeaning and harmful ways. These cartoons have largely disappeared from America's cultural memory, allowing younger generations to forget the toxic imagery that shaped the collective American imagination. While vestiges of racist representations still appear in modern comics and cartoons (such as the ongoing legacy of minstrel-like white gloves in animated characters), the pervasiveness of racial caricatures is often downplayed. In some ways, this erasure represents progress: overt racism is no longer as widely accepted. In other ways, however, it has contributed to a cultural amnesia that rewrites the history of racism in America, with ongoing efforts to paint the nation's past as more colorblind and progressive. By inadequately archiving the history of racist caricatures and diminishing their harm, this process deepens the erasure of America’s true racial history.

While I continue to debate the effectiveness of Crumb’s satire, I have started to view his work differently, having more context about his life and upbringing. In some ways, Crumb’s work vividly brings to life many of the critiques Toni Morrison presents in Playing in the Dark, particularly her analysis of how White authors' perception of blackness has shaped American literature and culture. In the book, Morrison explores how White American writers have constructed an "Africanist persona," using Blackness as a point of contrast to define themselves and their society. She argues that this construction is not just a peripheral detail but a central element of American identity, one that writers have relied on to define what it means to be White, human, and American.

Crumb, having grown up surrounded by racist portrayals of Black people, brings this idea to the forefront by exposing the inner thoughts of White Americans. Unlike the writers Morrison examines in her book, Crumb completely collapses the barrier between writer and reader, revealing that there is no neutrality or objectivity in the way White people portray marginalized groups. By amplifying caricatures, he strips away any attempt to soften the impact of these stereotypes, forcing the audience to confront their ugliness head-on. Crumb’s use of exaggeration and grotesque imagery is not simply an act of mimicry; it is a deliberate unmasking of the societal forces that shaped him. Returning to “Angelfood McSpade,” it’s clear that Crumb’s portrayal of a so-called “primitive” Black woman echoes the grotesque caricatures found in cartoons like Jungle Jitters, which trafficked in dehumanizing stereotypes of Blackness. His work reveals how deeply embedded these caricatures are in the White American psyche, suggesting that the “Africanist presence” Morrison describes is not confined to literature but saturates all forms of cultural expression.

Crumb turns to confession as a means of exposing the sins of his father and, by extension, the sins of the culture that produced him. In doing so, there is some hope in him that this public airing of evils might rid society of some of its most enduring ills. In an interview from 2015 with Alex Wood, Crumb discussed the deeply embedded racism in his work, acknowledging that he feels a compulsion to put his darkest, most uncomfortable thoughts on display. He said, “But somehow I almost feel like it has to be vented. Somebody had to do it, put that shit out there.” In this way, Crumb sees his work as a necessary exorcism, a way to unearth the toxic ideas that he, like many of his generation, had internalized growing up. Much of Crumb’s most transgressive and uncomfortable work emerged during the 1960s, an era that welcomed transgression after the repressive and stifled 1950s. His willingness to confront these issues in such an unflinching, raw way can be seen as part of the cultural moment, one that, while unsettling, forced the nation to grapple with its racial contradictions at a time when traditional structures of authority were being challenged.

Yet, even Crumb recognizes that there’s a limit to the transgressiveness. The changing racial attitudes in America have made his work lack some of its relevancy and he’s moved on from using overtly racist caricatures, though his work still retains a grotesque edge. The key takeaway for me after engaging with Crumb’s art is the importance of context. Understanding the historical and cultural backdrop of his work allows me to see the intentions behind it and the societal conditions that made it possible. Yet, there are many who take his work at face value, interpreting it most superficially. Crumb himself dismisses these interpretations as stupid, and he’s not entirely wrong. Still, it exposes a core weakness in his approach, which is that art should speak for itself. In a world where racial history and context are being erased with increasing speed, that assumption seems naive. Crumb's work may challenge, but without context, it risks being misunderstood or misappropriated, and that’s a responsibility he doesn’t seem willing to acknowledge or accept.

While I still can’t stomach most of Robert Crumb’s comics, I can now see how his art serves as a tool for understanding the world that the Boomer generation confronted. His art has also made me reconsider the lineage of cartoons and media more broadly. American popular culture remains deeply haunted by the racist and sexist tropes inherited from the past. These harmful images didn’t just disappear with time; instead, they evolved and were sanitized. The Civil Rights Era had many Americans wanting to quickly move on from a cruel racist past. There is a deep desire by many White Americans to distance themselves from the uncomfortable realities of their racial history, suppress the lingering scars of systemic racism and segregation, and even will a colorblind past into existence. This yearning for a sanitized narrative not only perpetuates historical amnesia but also allows these deeply ingrained prejudices to persist, albeit in more subtle and insidious forms. Crumb’s work, in all its grotesquerie, asks us to confront these dark undercurrents rather than letting them fester unchecked.

Crumb’s work also made me reflect on how much the racial reckoning of 2020 was a missed opportunity. It initially offered a promising moment for White America to confront its long history of racial violence, inequality, and denial. But rather than addressing this history head-on, it seemed many White Americans used the moment to further sanitize and erase the painful past. By posting Black squares, donating nominal amounts of money, and expressing performative grief, many felt they had paid their dues. Five years later, it feels as though we’ve slipped back into familiar patterns. There’s a growing urge across the political spectrum to sanitize the past, downplay the harm, or reframe historical injustices in more palatable terms. Among some White leftists, there’s also a tendency to reduce everything to class struggle—as if race, gender, and sexuality are mere distractions from the “real” issue. But race and sex are not peripheral; they are deeply embedded dimensions of class itself. When these factors are underexamined or dismissed, we are doomed to repeat the same cycles.

Crumb’s work, in many ways, serves as a grim reminder of what happens when that dark underbelly is left unexamined. His comics are like open wounds: grotesque, messy, and at times horrifying. But they also show what it looks like when someone confronts their inner rot directly. Confession was his salvation. Unlike his father and brothers, whose repression ultimately destroyed them, Crumb has survived—perhaps because he never stopped purging what poisoned him.

Ultimately, Crumb’s art serves as a reminder that the darkness of America’s racial history still lurks deep in the consciousness of many White Americans, particularly White men. Today’s culture wars and the resurgence of nostalgic longing for a “simpler” time are, in part, a reflection of those demons that America remains unwilling to exorcise. The ghosts of the past continue to shape our present, not as a distant memory but as a pervasive, ongoing influence. While I will continue to keep Crumb’s work at arm's length, engaging with it has been a useful exploration into the dark and twisted specters that plague the American psyche.

That’s all for this week. Thanks for sticking with me. I debated including the racist images referenced in this essay, but it’s hard to wrap your mind around the subject matter without these images. Thanks for reading! I’d love to continue the conversation so leave a comment.

So, do you like Crumb or not? Is he a great artist or not?